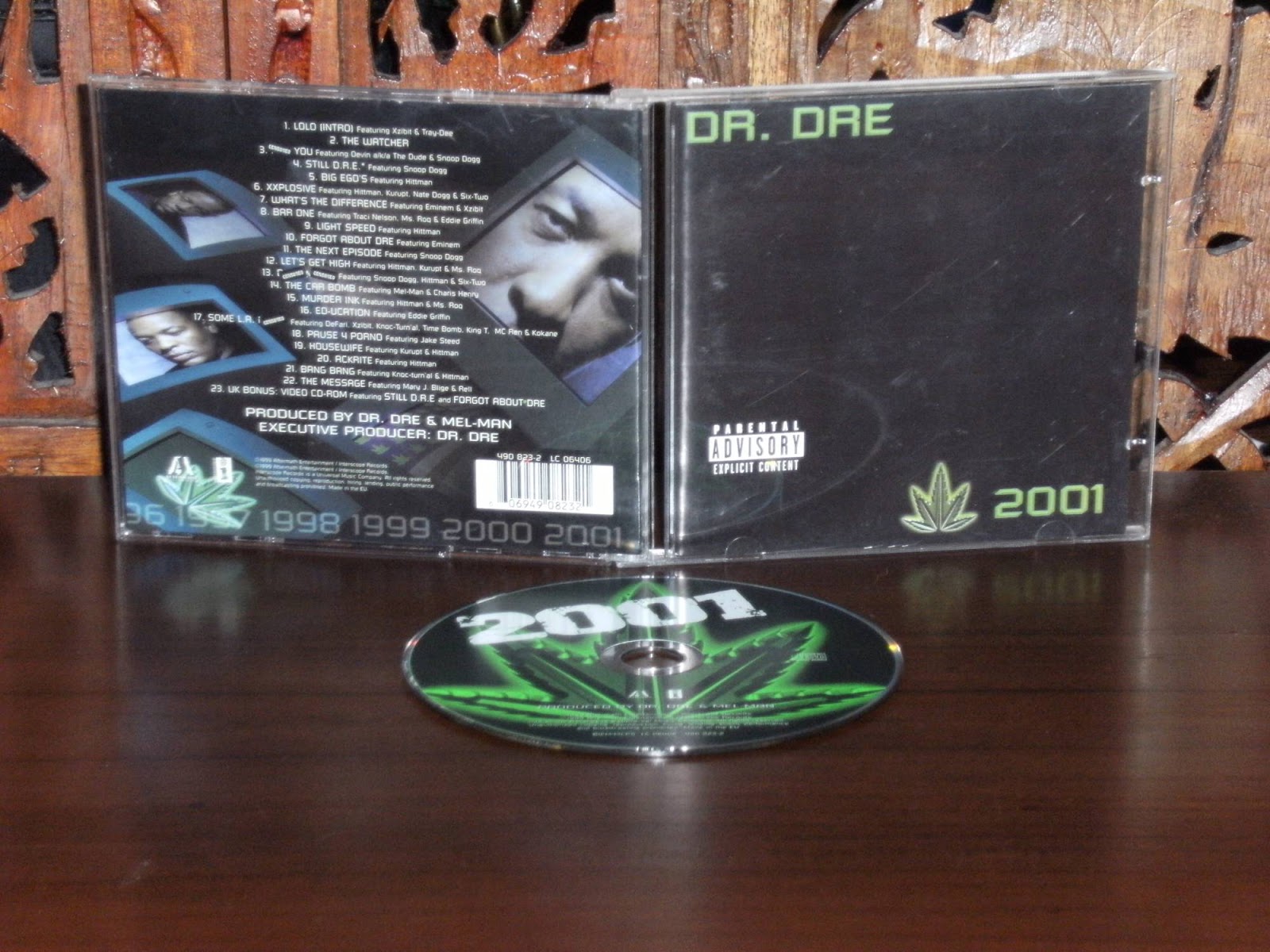

As a member of N.W.A in the mid-1980s, the producer was a star, but he was convinced that Eazy-E—the head of his record label, Ruthless, and fellow N.W.A. Dre’s solo rap career began like a yarn out of a mob epic: coercion, conspiracy, guns strategically placed near jacuzzis. Dre and Mel-Man, as well as Lord Finesse. The record was produced primarily by Dr. It was released on November 16, 1999, by Interscope Records as the follow-up to his 1992 debut album The Chronic. 2001 (sometimes referred to as The Chronic 2001, Chronic 2001 or The Chronic 2) is the second studio album by American rapper and producer Dr.

2001 is the follow-up to Dr. Dre.It was released on Novemby Interscope Records. Adding Photos / Videos2001 is the second studio album by American hip hop recording artist Dr. Select text to change formatting or add links. Begin typing in the editor to write your post.

The documents weren’t deemed legally binding, but the wheels were in motion. He told Eazy he had N.W.A.’s manager Jerry Heller tied up in a van before offering a final warning: “We know where your mother lives.” With that, Eazy signed. Suge delivered contract releases for several Ruthless artists and planned to squeeze Eazy into signing them so he could poach the artists for the fledgling label he was starting. In 2000 or 2001 Fafu joined the group as producer and DJ and the three started recording non stop.On April 23, 1991, Eazy-E went up to the studios at Solar Records where he was greeted by Suge and a small entourage of men with pipes and Louisville sluggers.

The Chronic became that cornerstone achievement, kicking off a historic four-year run that ended with the death of the label’s other major star, Tupac Shakur. On top of that, neither he nor Suge had much of a business acumen, and they were hemorrhaging cash.Death Row was ostensibly up and running with a master architect at the helm, but the young label needed a big victory upon which to build its empire. He was accused of a savage, public assault by journalist Dee Barnes and another assault on a police officer during a 50-person brawl he allegedly started. Five of the eight albums Dre produced for Ruthless from 1987 to 1991 went platinum, but he was a volatile figure prone to violence. Plagued by legal battles and beset with a number of open court cases, nobody would touch him. Dre was the biggest producer in hip-hop music, a pioneer drawing comparisons to Quincy Jones and Phil Spector he was also its most unemployable one.

The triumphant lead-off “Fuck wit Dre Day” couches celebration of his success in the broader context of the streets losing respect for Eazy. They are the album’s primary antagonists, and Dre’s ire for them powers his performance. It is so meticulously crafted, so magnificently designed.Thanks to some last-minute minute legal negotiations that set the price for Dre’s freedom from Ruthless at royalty payments for all of Dre’s Death Row projects including The Chronic, the same album Dre used as a megaphone to badmouth Eazy-E and Jerry Heller was also paying them handsomely. He collapsed the distance between the lawless Los Angeles of the persona he created for himself and the real one right outside Solar studios, giving his songs texture wherever possible: prank calls Rudy Ray Moore skits clips from blaxploitation flick The Mack an earlier Chronic song playing as background music for a sketch in a later one live commentary from protestors exasperated TV news anchors announcing a city on fire. His debut album, 1992’s The Chronic is an imaginative crusade with half-truths so vibrant they blurred the lines of what was real.

2001 Dre Album How To Spot Talent

The album sometimes plays as promotional material for the label, partially because everyone there was trying to will future success into existence, but also because the label was the center of Dre’s entire world at the time. In Ronin Ro’s Have Gun Will Travel, Heller lamented its loss: “That album would’ve been ours if it hadn’t been stolen.”Death Row was a seedy operation with drug lord investors, secret incorporations, and nefarious loans, according to Ben Westhoff’s Original Gangstas, but the men at the top both knew how to spot talent. Despite all the direct provocation, Dre’s greatest insult was the album itself: He’d pried The Chronic right out of Eazy’s hands.

He found his new scribe in Snoop Dogg, a slinky teenager from Long Beach who quickly became one of the greatest rappers ever.Dre wasn’t a songwriter, he’d only ever performed in a posse, and the hearty voice of the rapper he banked on, the D.O.C., had been irreparably damaged in a car accident. Those were big shoes to fill. In N.W.A, he had the luxury of working with one of rap’s best-ever writers, Ice Cube. I didn’t receive one fucking quarter in the year of ’92.” Dre desperately needed to find a new voice.

“I was whoopin’ niggas! They would be going home to go get chicken, I’d be in that motherfucker all night. “When I listen back to The Chronic album, I’m like, how the fuck was I on damn near every song?” Snoop remembered. He seized every opportunity. It was Snoop, with his sneering yet relaxed flow, that so casually stole the role.

The aromatic puffs of smoke that filled the studio inspired slower, smoother music.Snoop was at the center of a writer’s room that Dre had taken to calling the Death Row Inmates: The D.O.C., rapper-producer Daz Dillinger and RBX (two of Snoop’s cousins), Kurupt, Lady of Rage (who Dre flew in from Manhattan), Snoop’s group 213 with Dre’s stepbrother Warren G and a little-known singer named Nate Dogg, and the First Lady of Death Row, the R&B vocalist Jewell. Dre, who’d rapped on 1988’s “Express Yourself” that he didn’t smoke marijuana because it caused brain damage, was now naming his entire album after a potent cross-strain. His incessant use introduced his producer to the chronic, slang used in reference to sticky hydroponic bud that was of the highest quality the term, which became a metaphor for the quality of the music, stuck as a title. Before you know it, I’m on a song.”As both a purveyor and connoisseur, Snoop also brought to the table one of the album’s most critical ingredients: weed.

Songs like “Lyrical Gangbang” and posse cut “Stranded on Death Row” in particular had this battler’s edge, pure showcases of raw rap talent from Lady of Rage, Kurupt, and RBX. Every member wanted to cut the best verse and meet Dre’s impossibly high standards. The Inmates were all broke and eager to rhyme back then. Those battles spilled over to The Chronic, fostering both a familial closeness (beyond the obvious blood ties) and a competitiveness that fueled many sessions. According to Original Gangstas, the label head would send his rappers to little amphitheaters and housing projects to battle anyone.

If the former is an overstatement, the latter is true. Gold called his verses “forced,” and deemed him a lesser rapper than producer. They weren’t working as hard to be clever as most of the rappers back East, and while they weren’t quite the writers Ice Cube and MC Ren were, their verses were still striking, charismatic, imposing, and idiosyncratic.Criticism of the rapping on The Chronic also took aim at Dre, who was never quite a natural rapper, even in N.W.A’s heyday.

For six days after, in Spring 1992, L.A. The spark was an acquittal of the four officers caught on videotape beating motorist Rodney King with batons. Dre goes to painstaking lengths not to appear too frequently, and when he does, he comes off as part of a dynamic one-two punch.The force of the combination is felt most heavily on the attack, and much of The Chronic offensive continued N.W.A’s longstanding war with cops and L.A.’s violent policing initiative. One of the album’s greatest feats is how it mitigates his limitations with a chorus of other voices.

(As the city outside was catching fire, one woman at the dinner said of Gates, “We’re behind you all the way and I want to see you as President of the United States,” to laughter and cheers from the crowd. While the violence of the riots spread from the corner of Florence and Normandie like a wave overtaking the city, Gates was at a fundraising dinner in affluent Brentwood. Chief of Police Daryl Gates, who, in 1990, infamously said casual drug users “ought to be taken out and shot” because “we’re in a war,” had encouraged the kind of treatment seen in the Rodney King video across the city, and now that black citizens were rising up in response he was sitting on his hands.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)